Eat your vegetables, because only they can provide all the carotenoids needed by the body for many functions, including anti-cancer effects in the skin.

Carotenoids are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments produced by plants, bacteria, and algae. These pigments are important to human health, including the health of the skin, and must be acquired by diet. Carotenoids can also be fed to the skin topically. The outer layer of the skin is rich in carotenoids, and evidence finds that the sebum and perspiration naturally feed carotenoids to the epidermis. So well formulated topical products can feed the skin carotenoids too.

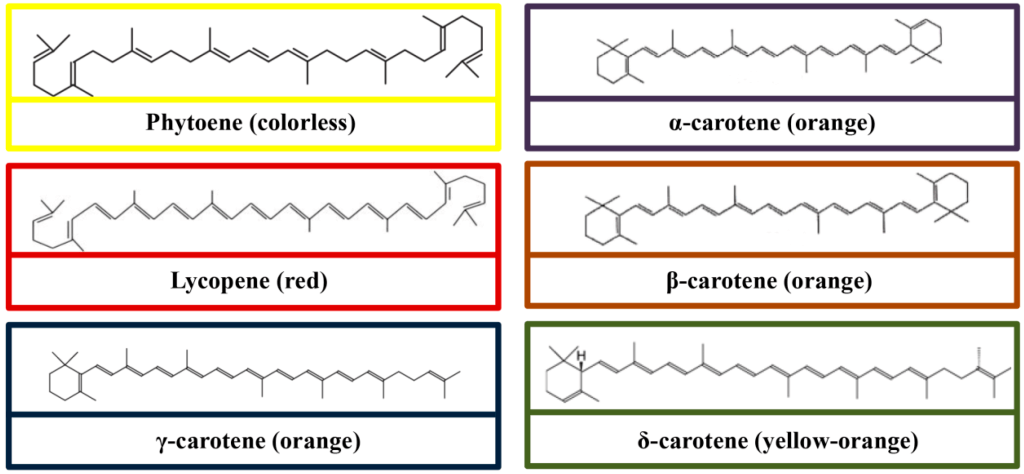

There are over 1,100 known carotenoids, which can be further categorized into two classes, xanthophylls (which contain oxygen) and carotenes (which are purely hydrocarbons and contain no oxygen). All are produced from 8 isoprene molecules and contain a backbone of 40 carbon atoms. The conjugated carbon chains of carotenoids quench singlet oxygen and other radical species. Carotenoids have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in our tissues. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of carotenoids have been found to aid in the prevention of a wide range of oxidative disorders, including arteriosclerosis, obesity, and various types of cancers. In general, carotenoids absorb light wavelengths ranging from 400 to 550 nanometers (violet to green light). This causes the compounds to be deeply colored yellow, orange, or red because the violet to green colored light has been absorbed by the pigment, leaving the longer, yellow to red wavelengths of light to be seen by our eyes. In autumn, when there are fewer daylight hours and temperatures are cooler, photosynthesis slows down and there is less chlorophyll production in plants. The reduction of chlorophyll reveals yellow and orange carotenoid pigments that are usually hidden by the abundance of chlorophyll present in leaves during the growing season. Carotenoids are the dominant pigment in autumn leaf coloration of about 15-30% of tree species. Certain carotenoids that contain unsubstituted beta-ionone rings (including β-carotene, α-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, and γ-carotene) have vitamin A activity, meaning these carotenoids can be converted to retinol in our skin.

From Tan et al (2019), molecular structures of carotenes (Phytoene, lycopene, γ-carotene, α-carotene, β-carotene, and δ-carotene).

And, molecular structures of some common xanthophylls (β-cryptoxanthin, zeaxanthin, lutein, astaxanthin, and fucoxanthin).

Human skin, is relatively enriched in lycopene and β-carotene types of carotenoids, compared with lutein and zeaxanthin. Dietary lutein and zeaxanthin are selectively taken up into the macula (central area of our retina where high contrast imaging occurs) of the eye, where they absorb up to 90% of blue light and help maintain optimal visual function. Unlike the other carotenoids, they are not precursors to retinol. Carotenoids are important components of the dark brown pigment melanin, which is found in hair, skin, and eyes. Melanin absorbs high-energy light and protects the skin from intracellular damage. β-carotene is an endogenous photoprotector, and its efficacy to prevent UV-induced erythema formation has been found in a number of studies. In the human skin, the highest concentration of carotenoids is found within adipocytes in the fat-rich subcutaneous tissue and in the stratum corneum (SC) within the lipid lamellae. The carotenoid concentration is not homogeneously distributed in the SC and has two maxima, occurring near the surface and near the bottom of the SC, which is explained by the two independent delivery pathways: from the inside due to blood circulation and keratinization, and from the outside with sweat and/or sebum secretion. Topical retinoid treatments inhibit the UV-induced, MMP-mediated breakdown of collagen and protect against UV-induced decreases in procollagen expression. Preclinical data indicate that carotenoids exhibit direct antimelanoma effect, and inhibit cell proliferation, cell migration and invasion in various melanoma cell lines grown in the lab. In a clinical study, topical carotenoids significantly enhanced skin hydration and elasticity, and reduced erythema, melanin and sebum contents over a 12 week treatment period. Several studies have observed positive effects of high-carotenoid diets on the texture, clarity, color, strength, and elasticity of skin. Beta-carotene supplementation altered skin color to increase facial attractiveness and perceived health in humans.

Let’s go a little deeper into the science when we consider our exposure to sunlight. UV radiation from the sun causes the production of free radicals in our skin. Free radicals can be particles, atoms, or molecules that have one or more unpaired electrons on the outer valence shell. This condition changes the chemistry of the molecules in our skin making them chemically very reactive. The free radical molecules try to regain their missing electron by obtaining it from the surrounding molecules. If the electron is obtained, the “stolen” electron leaves the donor molecule in a damaged state. Most free radicals contain oxygen, so they are called reactive oxygen species (ROS). The most common ROS in the biological tissues are superoxide anion radicals (O2•−), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and singlet oxygen (1O2). Also occurring are reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and lipid oxygen species (LOS) can be developed, such as lipoperoxynitrite radicals (LOO•), causing lipid peroxidation reaction cascades, inflammatory responses, and DNA and protein damage. Oxidized lipids, similar to old, rancid cooking oils that you’ve been warned not to use, can be toxic and act as lipid radicals or oxidants. The interaction of the ROS hydrogen peroxide with iron (Fenton reaction) causes chronic inflammation, sometimes leading to Ferroptosis, a form of programmed cell death. The interaction of ROS and RNS with biological molecules and cells may cause irreversible damage to their structure, which may lead to cellular dysfunction. Most of the oxygen we breath and that is consumed by cellular mitochondria in the multistep processes of oxidative phosphorylation is converted into water, while a small fraction can diffuse out of the respiratory chain as ROS and RNS. ROS and RNS are able to permeate the skin, including the stratum corneum (SC). Plasma medical procedures that damage the skin depend on this mechanism. Therefore, whether the damage is intentional, such as a medical procedure, or unintentional, such as too much exposure to the sun, carotenoids are a critical part of better preventing and remediating such damage through their antioxidant effects.

The human body, including the skin, contains a balanced set of antioxidants that can be divided into two main classes—endogenous and exogenous antioxidants. The major enzymatic endogenous antioxidants include glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase. Non-enzymatic endogenous antioxidants include glutathione, lipoic acid, uric acid, coenzyme Q10, vitamin D, intracellular reducing agents nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP). Exogenous antioxidants enter the human organism primarily by nutrition (dietary antioxidants), such as carotenoids; vitamins A1, A2, C, and E; polyphenols (including flavonoids); zinc; and selenium Because different types of antioxidants act in synergy, significantly increasing the number of neutralized free radicals and thus improving the efficiency of antioxidant protection, ingesting and topically applying a wide variety of antioxidants, including carotenoids, is important for skin health.