Scientists have known for decades about the benefits of natual peptides derived from our diets. However, topically applied synthetic peptides are eaily broken down in the skin and have considerable difficulty penetratring the stratum corneum, both of which degrade their bioactivity. Some peptides have a high molecular weight, many are hydrophilic in character, and are highly susceptibility to enzymatic degradation, requiring the application of formulation technologies to improve the stability and the penetration of peptides through the skin. On the other hand, natural peptides produced by the human body have developed protection and functional mechanisms. If you’re using S2RM from NeoGenesis, you’re using these natually produced peptides. Learning lessons from mother nature, a few science-based companies have followed nature and are attempting to develop biomemetic peptides that are “protected and functional peptides.” Too bad most cosmetic companies don’t know about and don’t use these “protected and functional peptides.”

Written in the journal, Future Drug Discovery, “Peptides have traditionally been perceived as poor drug candidates due to unfavorable characteristics mainly regarding their pharmacokinetic behavior, including plasma stability, membrane permeability and circulation half-life” (Christina Lambers, 2022).

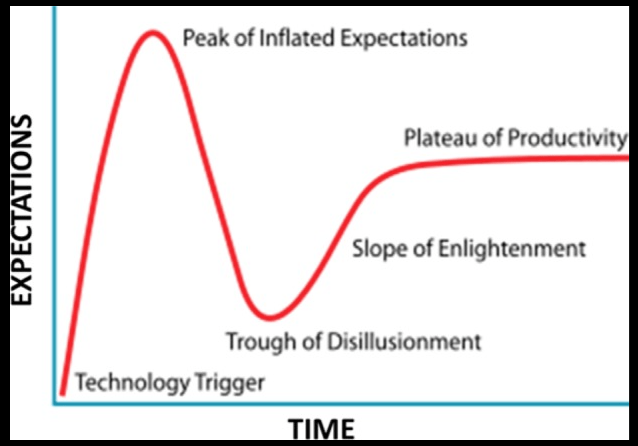

Peptides, along with exosomes, are “one of the skincare industry’s favorite ingredients right now,” Vogue reported in December 2024. At a Clinique launch event in early 2024, a physician declared peptides to be “the buzzword of the year.” The fashion of peptides seems to be at its peak hype (Fig.1): “Skincare is in its peptides era,” the beauty and fashion website Hypebae announced last month. As I am often asked about peptides, and because most of the literature for the lay public about peptides is incomplete and just plain wrong, I offer my short intro to peptides here. My blog is “sciencey” because it has to be in order not to present peptides in a manner that is not superficial and presents simplified dross.

.

From Maguire (2016)

What are peptides?

Basically, they’re short strings of amino acids (less than 50 amino acids). By contrast, proteins are long strings of amino acids. Peptides can be naturally produced or synthetically made in a laboratory. Naturally produced peptides are synthesized in the body as large precursor molecules (i.e., preproproteins) and are post-translationally (after the proprotein is made) processed and cleaved by proteases to generate their active peptide product. Synthetic peptides are typically made in the lab using a solid-phase peptide synthesis process where one amino acid at time is added to the string.

Problems with Synthetic Peptides

Synthetic peptides have many issues: off target activation of pathways that are detrimental to human health, poor targeting of beneficial pathways, poor penetration, and rapid degradation. Further, these synthetic peptides typically undergo lyophilization, a harsh freeze-druing process that disrupts their structure and further disrupts their safety and efficacy. Peptide aggregation and consequent loss of function is one of many problems in using synthetic peptides.

Further, the chemical synthesis process used to create peptides may introduce impurities or byproducts that can potentially lead to adverse reactions and toxicity issues. As stated in a journal from the American Chemical Society, “the current state of the art in peptide synthesis [synthetic peptides] involves primarily legacy technologies with use of large amounts of highly hazardous reagents and solvents and little focus on green chemistry and engineering” (Isidro-Llobet et al, 2019). Further, Varnava et al (2019) report that, “To date, the synthesis of peptides is concurrent with the production of enormous amounts of toxic waste.” In other words, the current industrial-scale peptide synthesis methods involve using substantial quantities of hazardous reagents and solvents, some of which may contaminate your topical product, while much of it pollutes the environment.

Synthetic peptides are cheap to make, and can easily be made in large quantities. That’s a plus for the compnies making them. But synthetic peptides can be problematic for therapeutic interactions that require post-translational modifications that are difficult to incorporate synthetically, such as glycosylation, for biological activity. Difficult to create disulfide linkages, important for the functional attributes of peptides and proteins. And peptides lack efficacy in biochemical pathways where the secondary or tertiary structure is critical or in making larger bioactive peptides and proteins. Natural peptides and proteins don’t suffer from these problems.

Microproteins ( you haven’t heard about these because they’re newly disovered) are Different from Peptides

You haven’t heard about these small proteins because they’re newly discovered and very difficult to identify and characterize. Microproteins are typically less than 100 amino acids (AAs) in length, but are different from peptides because they are not cleaved from a proprotein or protein. Until recently, microproteins have evaded detection because traditional genome annotation methods relied on stringent rules to distinguish protein coding RNAs versus non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) to minimize the discovery of false positives including a minimum ORF length of 300 base pairs (bps). This ad hoc 100-codon threshold was initially selected based on the calculated probability that ORFs over 300 bps are significantly more likely to encode stable proteins. sORF-encoded microproteins have emerged as important new players in cellular biology and physiology, and they continue to be identified at high rates. To be clear, microproteins are polypeptides originating from short open reading frames (sORF) of less than a hundred codons. For a long time, they have been understudied because it is difficult to distinguish coding from non-coding sORFs. In recent years, the number of putatively translated sORFs has been narrowed down from hundred-thousands or millions to various thousands, owing to the advent of ribosome profiling and advances in bioinformatic and proteomic techniques. Therefore, efforts are now being made to include sORFs with robust translation evidence into databases such as GENCODE. The field of microproteins has since steadily grown, though it is still unclear how many functional coding sORFs exist in the human genome, and relatively few microproteins have been characterized to date.

Microproteins are made in adipose mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) and likely released for therapeutic effect by the ADSCs (Bonilauri et al, 2021). Because of the past difficulty in identifying these microproteins, they are just now receiving attention for their therapeutic value. Understand, microproteins likely provide therapeutic value to the ADSC secretome, but our understanding of this is in its infancy.

Natural Peptides Drived from Diet

Lunasin is a 43-amino acid polypeptide originally discovered in soy. Research into the properties of lunasin began in 1996, when researchers at the University of California-Berkeley observed that the peptide arrested mitosis in cancer cells by binding to the cell’s chromatin and breaking the cell apart. The name of the peptide was chosen from the Tagalog word lunas, which means “cure”. Since its discovery, scientists have identified lunasin as the key to many of soy’s documented health benefits and it has been studied for various benefits, including cancer prevention, cholesterol management, anti-inflammation, skin health, and anti-aging. Lunasin exhibits different biological and chemopreventive properties including anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, antioxidant and immune-modulating properties, anti-atherosclerosis, and osteoclastogenesis inhibition potential. Sounds great, right? But there’s a catch. Lunasin as part of a whole soy diet confers health benefits and is bioavailble, measured in human blood, but isolated lunasin has not shown such beneficial results. Isolated peptides don’t work as well as those peptides in their natural state. This is but one of many examples of natural peptides that are derived from a healthy diet providing benefit in their natural state, but when isolated, not so much happens.

Conjugated Peptides

The the human body, peptide conjugation is a crucial process involving the attachment of chemical entities to peptides to enhance their safety, efficacy, and pentration properties. These modifications, called post-translational modifications, can significantly improve characteristics like stability, targeting, and half-life of the peptide within the body, including the skin. Without peptide conjugation, the peptide is bare, subject to rapid degradation, and hydrophilic (meaning loves water and hates fat) so that it is repelled by the fatty nature of the stratum corneum. These are the problems with most synthetic peptides – they’re not conjugated. They’re not biomemetic but are cheap and can be easily hyped during the peak of the peptide-hype curve, i.e. peak of inflated expectation. However, synthetically conjugated peptides often don’t work well either.

For example, Palmitoyl Pentapeptide-4 is a conjugated peptide (pal-KTTKS). The molecular weight of Palmitoyl Pentapeptide-4 is 802.068 g/mol, larger than the “500 Dalton rule.” It consists of a pentapeptide (a chain of five amino acids, KTTKS) linked to a palmitoyl group, which is a fatty acid. This conjugation somewhat enhances its ability to penetrate the skin and makes it more effective as an anti-aging ingredient. However, Choi et al (2014) found that although pal-KTTKS was more stable than KTTKS, in dermal skin extract, 9.7% of pal-KTTKS remained after 120 min and 11.2% of pal-KTTKS remained at 60 min in the skin homogenate. In the epidermal skin extract, the concentration of pal-KTTKS throughout the 120-min incubation period was almost similar to its initial concentration. Lower amounts of proteolytic enzymes in the epidermal skin extract than in the dermal skin extract and the skin homogenate may account for pal-KTTKS lasting longer in the epidermal skin extract.

Natural Proteins and Peptides Penetrate the Skin Better than Synthetic Peptides

Palmitoyl Pentapeptide-4 (PP-4), a conjugated peptide. Choi et al (2014) found only 11% of the peptide remains after 60 minutes in a homogenate of dermis – it’s broken down to be ineffective. Further, in skin permeation experiments, no detectable levels of KTTKS and pal-KTTKS (PP-4) were observed in the skin over a period of 48 h – the peptide dosen’t penetrate the skin.

Contrast this to the stem cell released molecules (Secretome) of ADSCs that do penentrate the skin and activate collagen production and a number of other beneficial physiological pathways. The secretome from ADSCs is loaded with proteins, peptides, microproteins, microRNA (not mRNA or DNA) and other beneficiary molecules. They work effectively, as mother nature intended, doing so collectively so that the mutlitude of molecules working togther, a systems therapeutic, exhibit synergistic, beneficial effects.

Summary

Synthetic peptides are all the rage now in skincare. Too bad most of them offer much hype and little or no benefit. There are some newer, more sophisticated conjugated peptides that I’m testing to determine whether they exhibit better efficacy than the current conjugated peptides. Stay tuned.